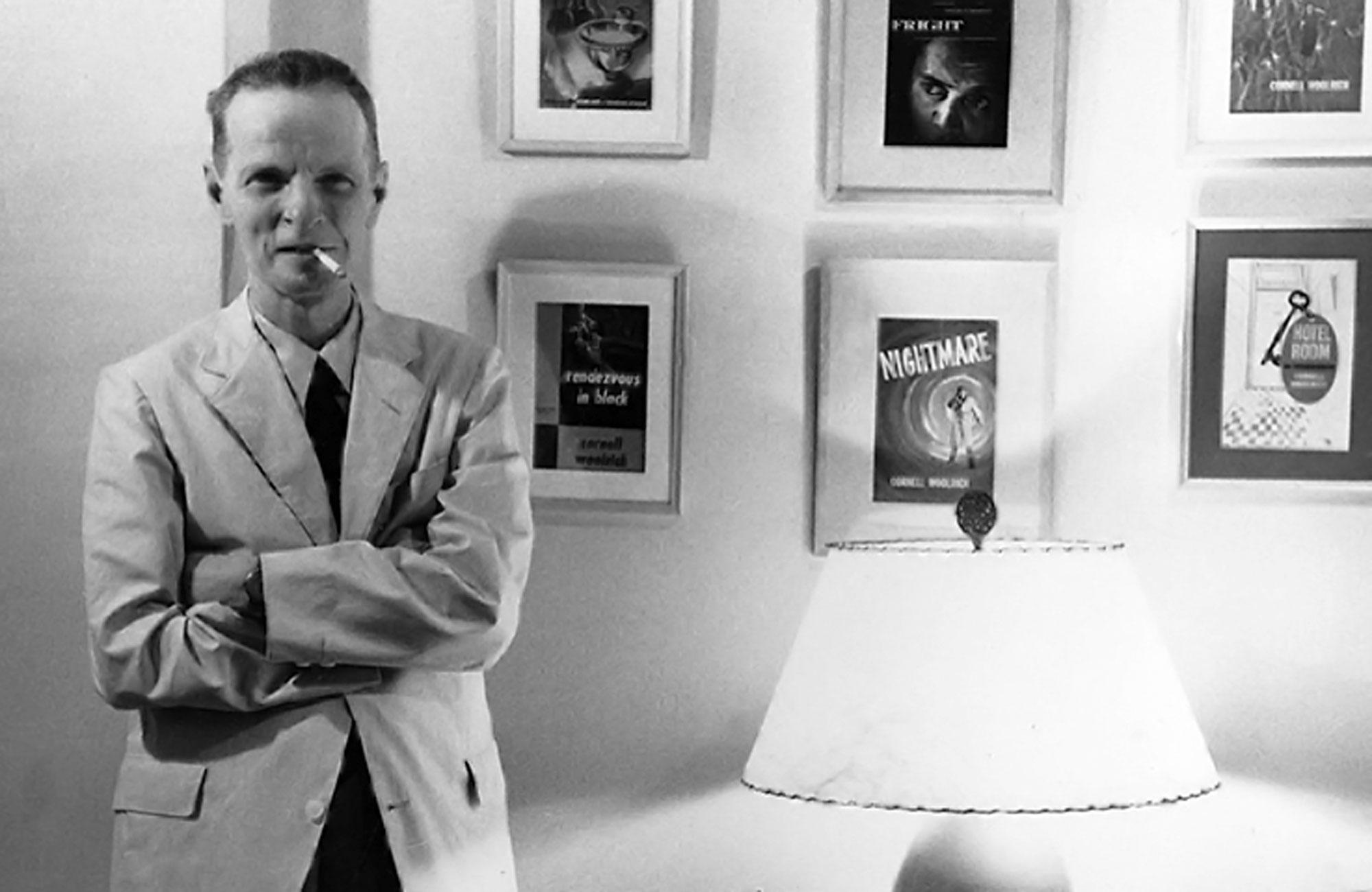

Many fans and critics consider Cornell Woolrich to be the literary father of film noir not only because more of his works were adapted for the cinema than any other writer’s (and it’s not even close) but also because his prose was unique in creating the mood of noir.

Other scribblers perfected the hardboiled style, which, of course, influenced the noir attitude and especially the dialogue, but Woolrich, with his more deeply psychological points of view, with his use of thrillingly visceral imagery and metaphor, and with his often elliptical plots that jumped from head to head, coated his stories with a blanket of alienation, a slow suffocation.

Writing in his autobiography, Woolrich described his childhood feelings when it dawned on him that he would one day die: “I had that trapped feeling, like some sort of a poor insect that you’ve put inside a downturned glass, and it tries to climb up the sides, and it can’t, and it can’t, and it can’t.” Is there a more apt description of the noir ethos?

Here’s an example of how such a mind hit the page:

Does it do you good to know you’ve got us, you’ve wrecked us, a little fellow and a little girl like us? The odds were fair and square, weren’t they? Like they always are when you’re involved, you top-heavy, bone-crushing bully.

Such is the description of the city in Woolrich’s 1944 novel, Deadline at Dawn, published under the pseudonym William Irish, which takes place in a single night: a young man has one night to solve a murder and clear his name. Down-on-his-luck Quinn, having robbed a rich man’s safe, meets pretty dance hall girl Bricky and forms an instant bond when he learns they’re from the same hometown back in Iowa. Both having failed in the big city, they make a pact to return to Iowa on the first bus in the morning but not until Quinn rights his wrong. But when they secretly enter the victim’s home that night to return the cash, they discover his murdered corpse, which launches a frenzied quest to find the killer before Quinn is roped in as a suspect.

While the characters’ motivations aren’t always clear and the time constraints are self-imposed, the novel is a thrill, hitting its stride about a third of the way in, the brisk pace never letting up as the young, sleuthing couple is entangled in a deadly blackmail scheme. Woolrich masterfully inserts suspense, several scenes genuinely spine-tingling in the thick of the night, and his gift for menacing metaphors is on full display in passages like:

Smoke suddenly speared from her nostrils in two malevolent columns. She looked like Satan.

And:

The blow, when it came, was rapid and with a sound like a paper bag full of water dropping from a third-story window.

Deadline at Dawn was adapted to film not once but twice. The 1946 RKO version was the only film directed by prolific Broadway theater director (and husband of legendary acting coach Stella Adler) Harold Clurman, whose theatrical flair took advantage of the high-gloss studio sets of RKO, which by this time had mastered (some might say invented) the visual aesthetic of film noir.

Starring the magnetic Susan Hayward and the serviceable Bill Williams, Clurman’s film deviates significantly from the novel, adding a memory loss premise, changing the murder circumstances, and introducing a third amateur detective in the form of philosopher-cabbie Gus played by Paul Lukas. With camera work by the masterful Nicholas Musuraca, the film impresses visually more than narratively.

The more exciting — and more faithful — adaptation comes from the other side of the world and the other end of the noir cycle: 1963’s Ten to One (Bire on Vardi) was directed by Turkish director Memduh Ün in between his other late-cycle noirs, Death Stalks Us (1960) and Before the Law (1964). Following Woolrich’s novel almost to the page, this version’s low budget starkly contrasts with RKO’s high-end production values, offering up a sleazier atmosphere from the opening scene, the look and feel far more realistic aside from the stop-and-start jazzy score that swells and crashes abruptly and rarely matches the action on screen (bad scoring was characteristic of Turkish films at this time).

More amateurish yet somehow more mature than Clurman’s film, Ten to One seems to have more fun too: the murder victim lives not in an apartment but in a cavernous, multi-story townhouse of sorts, long corridors and creaky doors used for maximum suspense at night, the thick-mustached, woman-beating villain shot with extremely low-key lighting at close-up to look extra monstrous.

It’s a shame that neither film has been properly preserved on home media; indeed, Ün’s version is only available in terrible, tattered quality in the far corners of the Internet. But maybe this is a blessing in disguise since Woolrich’s source novel is far and away the most enjoyable way to take in Deadline at Dawn. And we’re all in luck! As part of their new, extensive series of Cornell Woolrich volumes, American Mystery Classics published a perfectly fine paperback edition just last year.

Mike Bayer is the creator and founding editor of Heart of Noir. His full bio can be found here.

© 2024 Heart of Noir