In the 1970s, a group of directors, fresh out of university programs, created the New Hollywood. John Carpenter, Francis Ford Coppola, Brian De Palma, George Lucas, and Steven Spielberg re-visited old genres, putting their own reminiscent spins on narrative. Their esthetics were grounded in nostalgia, re-vitalizing the western, the gangster picture, Hitchcock thrillers, Saturday cliffhangers, and horror and SF yarns.

Robert Altman, born quite a few years earlier, made his mark not in nostalgic nods to the past but in generic transformations. His The Long Goodbye (1973), built on the scaffolding of Carol Reed’s The Third Man (1949), re-considers noir definitions of identity: the detective as hero and representations of masculinity.

A salient feature of 40s and ’50s noir is man alone, the alienated hero. Both Holly Martins of The Third Man (1949) and Philip Marlowe of The Long Goodbye (1973) are fish out of water, men displaced from the time periods or cultures they swim in. American southerner Martins is suddenly dropped into an alienating post-war Vienna. A writer, and disciple of Zane Grey, Martins’ concepts of masculine heroism are linked to the westerns he has read and pens. And they don’t fit in Vienna.

When Inspector Calloway tells Martins to go home, that his friend Harry Lime was “the worst racketeer” imaginable, Martins mixes the historical fiction he writes with the historical reality he is presented with. He sees Calloway as a “corrupt sheriff,” trying to victimize Lime. Calloway, aware of Martin’s sentimental leanings and failed perspective, says, “So you’re going to find me the real criminal. Sounds like one of your stories.”

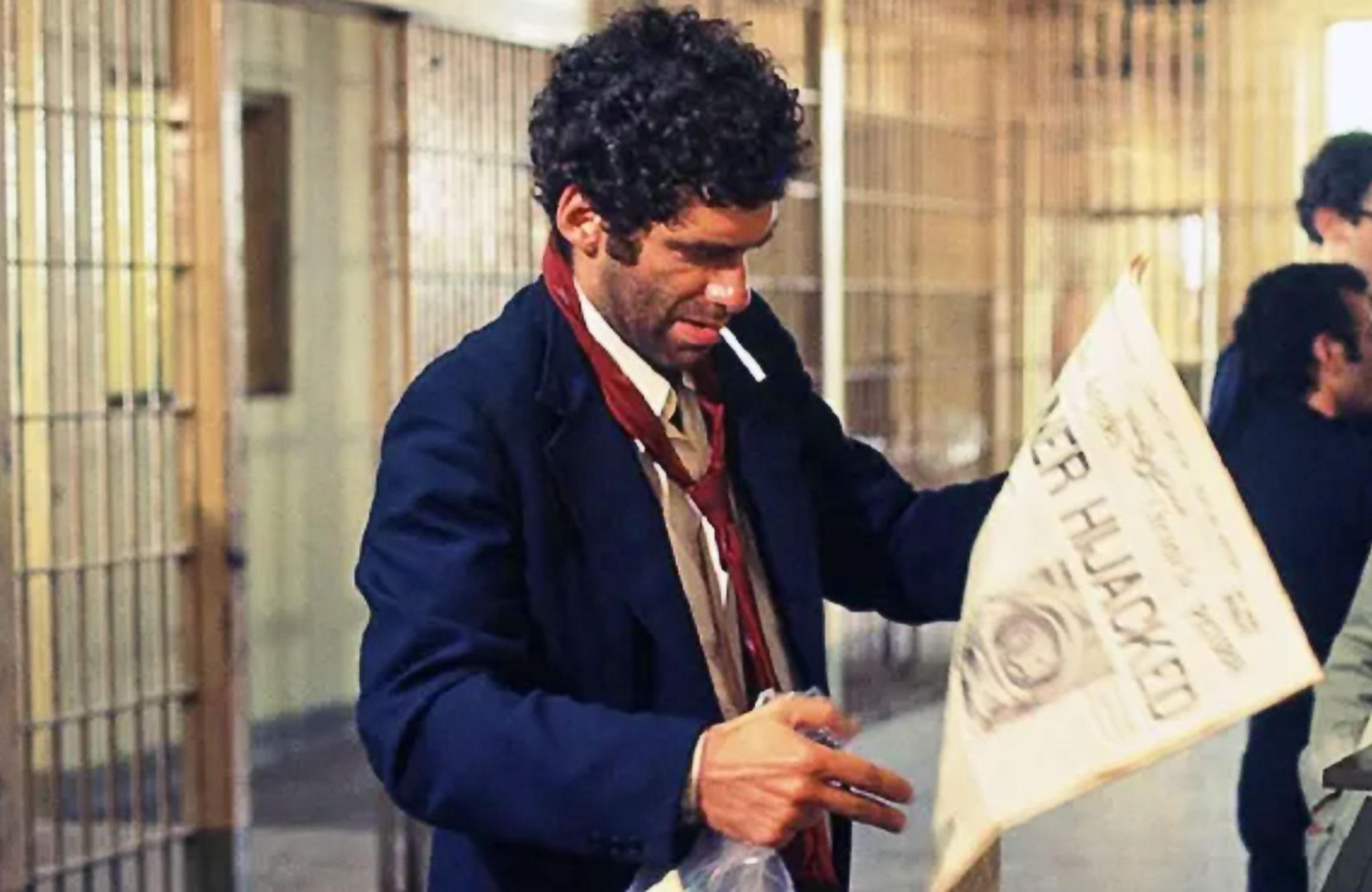

Marlowe, in his blazers, pressed shirts, and ties, belongs to the button-down American culture of the 1940s, not the hippy haze and casual California cool of the 1970s. By the ’70s, the American Cancer Society, through a series of strong PSA’s, documented the dangers of smoking, forcing big Tobacco to pull television advertising. But Marlowe is a throwback, a man out of time. He smokes in almost every scene (no one else in the film does so).

Marlowe is even nicknamed the Marlboro Man by one of the film’s chief suspects, Roger Wade. No doubt a nod to Marlowe’s Bogarting of cigarettes, but Wade is also acknowledging Marlowe’s westerner-type loner status. The PI often mumbles, like a live-action Popeye, his bottled-up feelings, repeatedly saying, “It’s alright by me.” Marlowe also drives a 1948 Lincoln Continental, and refers to a dog sitting in the middle of the street as Asta (Nick and Nora Charles’s dog of the Thin Man pictures). Marlowe’s cultural references and the costumes and props he inhabits are stuck in noir’s irretrievable past.

Like Holly Martins, Marlowe steadfastly believes in the innocence of his friend, Terry Lennox.

Noir protagonists often undergo a pyrrhic journey. What they discover on their quests causes them to figuratively die a little. Both men believe in the innocence of their friends, but as their two stories unfold the weight becomes unbearable. Martins learns that Lime isn’t dead and that Lime stole and then diluted penicillin to sell on the black market. The diluted penicillin led to the deaths of children and the “madness” of others. A defeated Martins confesses, “I knew him twenty years. At least I thought I knew him.”

In one of the film’s most memorable scenes, Martins (Joseph Cotten) meets Lime (Orson Welles) on a ferris wheel and the racketeer, with jaunty charm, disabuses Holly of his sentimentalized readings of manhood: “The world doesn’t make heroes like the kinds in your stories.” About the people down below, Lime says, if I offered you money, “would you feel anything if one of those dots stopped moving forever?”

Marlowe, loyal to a fault, spent three days in police lockup, refusing to give the police any information on driving Terry to Tijuana. But as evidence mounts, Marlowe discovers that Terry faked his suicide, is holed up in Mexico, and is awaiting the arrival of Eileen Wade, his lover and co-conspirator. When Marlowe confronts Terry over murdering Sylvia, Terry callously intones, “Well I wouldn’t call it murder.” Marlowe with gravelly disapproval says, “I saw the photographs, boy. You bashed her face in.” Terry’s response: he has a girl who loves him, a wife who wouldn’t let him go, so killing Sylvia was “goddamn simple.”

A narrative subtext to noir is uncertainty. We and our central protagonist are always on guard, never fully trusting the people we encounter. As the stories around Martins and Marlowe become more certain, each man reacts differently. Holly works with the authorities to bring down Lime; Marlowe, true to the PI’s lone wolf tradition, takes matters into his own hands, fulfilling Altman’s revisionist strategy of generic transformation.

Martins becomes a westerner in the film’s final scenes. It’s as if he steps right out of the pages of Owen Wister’s The Virginian. After Sgt. Paine is killed by Lime, Holly picks up the sergeant’s gun and determinedly heads down the sewer’s dark tunnels for a final showdown with Lime. Earlier, Martins told Calloway “don’t ask me to tie the rope,” but now like Wister’s hero who must hang his friend for stealing a horse, Martins metes out frontier justice.

The moment is wonderfully defamiliarized by Welles’s acting. During his final scene with Cotten, Welles narrowly nods with his eyes, imploring his best friend to execute him. Martins complies.

By contrast, Marlowe who has been thwarted throughout the film by the duplicitous Wades, pushed around by the police and gangster Marty Augustine, has had enough. Feeling somewhat impotent in a world in which his retro sensibilities hold no sway he lashes back, transforming into a Dirty Harry icon shooting an unarmed Terry and spitting with disdain after leaving Lennox’s body floating like a Jay Gatsby protege in a Mexican pool.

Things are no longer “alright by me.” Holly Martins commits a mercy kill; Philip Marlowe a cold kill.

Altman’s ending outraged critics at the time of the film’s release. They saw this killing choice as an affront and many charged Altman and writer Leigh Brackett (who had a hand in writing Howard Hawks’s earlier Marlowe film, The Big Sleep) as holding the genre in contempt.

Altman, always an iconoclast, bookends his film with Johnny Davis’s 1937 recording of “Hooray for Hollywood.” It plays before the opening and closing credits. It’s Altman’s way of winking at us, letting us in on an ironic joke: this film is no paean to old-time nostalgia.

Altman’s revising of what came before couldn’t be made clearer when comparing the endings of both films. In The Third Man, Holly arrives to see Lime buried a second time (this time it is his body in the grave). He leaves, via jeep, with Calloway for the airport. On the way Martins asks Calloway to let him out. Something has to be done for Anna. Lime’s girlfriend walks toward the camera, between a row of trees, leaves gently falling. Holly stands, in a tableau right out of D.W. Grffith, waiting, hoping. He lights a cigarette, the leaves continue to flutter down, and Anna fails to acknowledge him, walking right past him and the camera. Martins tosses aside his match. Fade to black.

Powerful and poignant, this ending is full of the weight of personal responsibility, of loss, and unrequited love.

Altman inverts these images to a much different end: his film too has a woman, a jeep, a man, and trees lining opposite sides of the road. But the mood here isn’t one of unrequited love and alienation, but of vengeance and twisted celebration. Instead of Anna walking toward the camera, Marlowe walks toward and past the jeep, making no eye contact, but his muscular walk is full of subtext and menace. Eileen grasps the undercurrent and rushes off in the direction of Terry. After she exits, Marlowe dances a celebratory little jig, and the final credits roll.

Hooray for Hollywood, indeed.

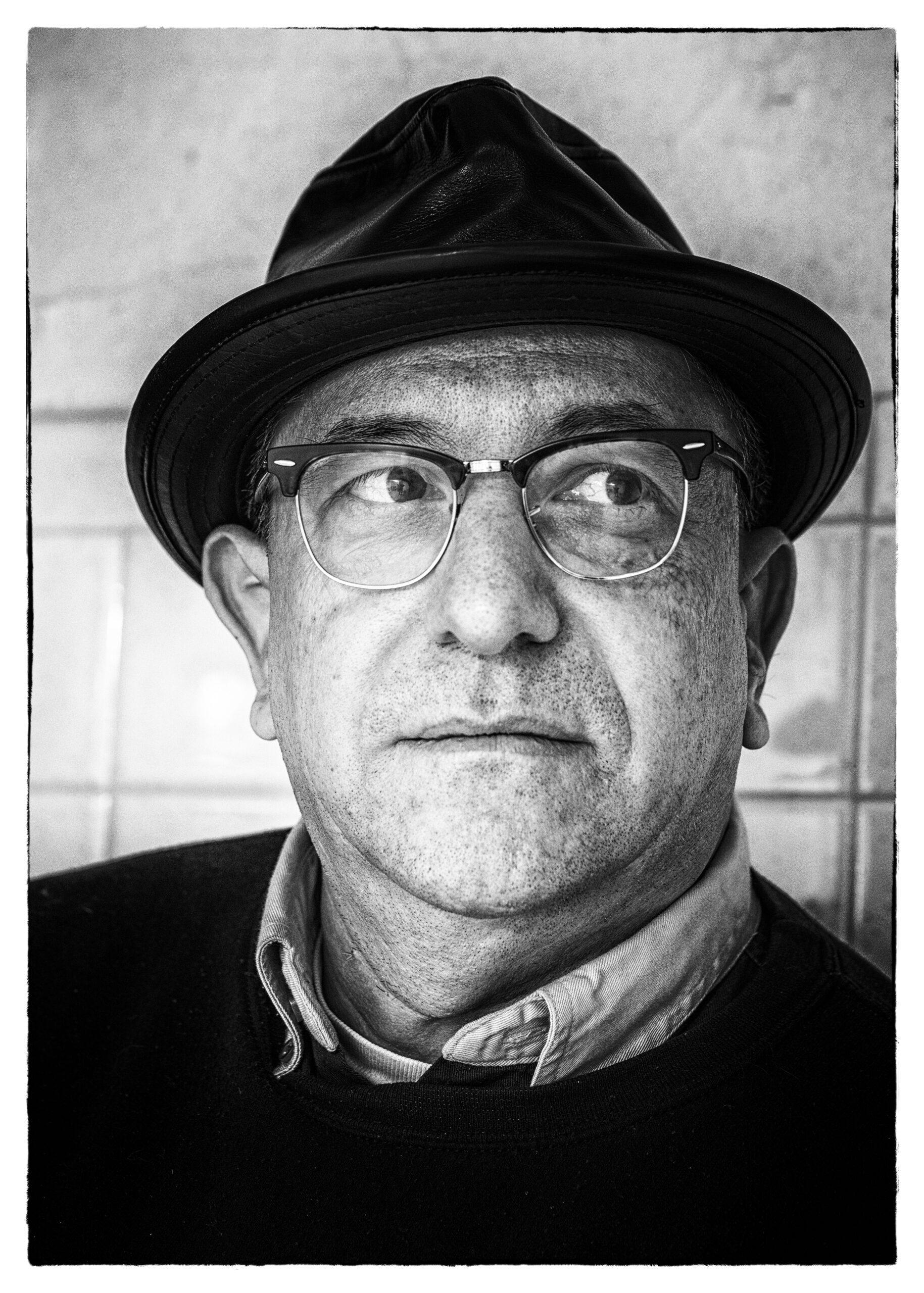

Grant Tracey teaches film and creative writing at the University of Northern Iowa and edits the North American Review. In 2021 he was a recipient of UNI’s Graduate College Distinguished Scholar Award. He has written articles on The Big Heat (1953), Samuel Fuller, and James Cagney. He’s author of the Hayden Fuller Mysteries. A brand new Fuller novel, A Shoeshine Kill, is due out next spring.

© 2024 Heart of Noir